I Should Have Killed Him Then Part 3

Dear Loyal readers,

Here is he eagerly awaited conclusion to Theresa Kennedy

Dupay’s study of the 1941 Johnson-Chase shootings. Theresa is a very thorough

researcher and I am always glad to have her help here at the Slabtown Chronicle. This story is put

into its historical context in my new book Portland on the Take now available from the History Press. -- JD Chandler

Captain H.A. Lewis, who

investigated the shooting at the East Precinct, detailed the various times Lt.

Johnson had cause to suspend Blaine Chase, but chose to do nothing. It seems

apparent that Johnson was avoiding some kind of possible confrontation that he

knew would explode if he did exercise his authority and power

over Patrolman Chase, his onetime partner of the 1920's. Ultimately, Johnson's

avoidance of Chase's blatant disregard for protocol forced Captain Lewis

to order Johnson to suspend Chase. Johnson was instructed to

suspend Chase because Johnson was Chase's immediate superior and any form of

discipline would have to come from him. Captain Lewis also ordered

Johnson to inform Chase that the suspension had really come from him, and

not Johnson, as if that admission might ameliorate the sting of the suspension.

Tragically, it was still Johnson who had to approach Chase the week before the

crimes, to inform him of the suspension that would take place, knowing as he

would that Chase would explode in a fury. It seems inexplicable why anyone in

the bureau would have forced these two men to work together, given their past

history, which most of the older rank and file had to have

been aware of.

Captain Lewis, a native

of England, had signed on with PPB in 1911. The bureau was much smaller then,

Lewis had to have been more than cognizant of the betrayal

Chase had suffered at the hands of Johnson back in 1922. And yet in the

following excerpt from his written report to Chief Jenkins, Lewis ignores the

real issue regarding the true motive for Chase’s attack on Johnson and offers a

superficial reason as to Chase's longstanding bitterness and resentment.

“During the past nine

or ten months his continued absence without leave has grown to the point that I

instructed Lieutenant Johnson to take some action. When he spoke to Chase about

it, Chase flew into a rage and accused the Lieutenant of picking on him. This

was about the middle of March. I told Lieutenant Johnson to tell Chase it was

my order that the next time he was A. W. O. L. he would be suspended for three

days and that if he was not satisfied I would file charges against him. Upon

receiving this information he again flew into a rage at Lieutenant Johnson and

accused him of discriminating against him, although he knew this was my doing.

However, the Lieutenant saw fit to overlook the matter again and let it ride

until Chase deliberately absented himself for three days without so much as a

phone call. I instructed the Lieutenant to suspend him for three more days.

When this was done he flew into a rage and bawled the Lieutenant out with the

result that I did file charges against Chase and told him that I would

personally appear against him with the hope that the Disciplinary Board would

teach him a lesson. He appeared to have no resentment toward me particularly

but evidently blamed the Lieutenant for all his trouble and worked himself into

the frame of mind which ended in the shooting. I have no doubt that Chase's

general physical condition, and the fact that he was always surly and

bull-headed under any restriction or discipline, contributed largely to the

breaking down of a mind which, in my opinion, was never restricted by any

self-discipline and was never exceptionally strong. This is my conclusion and

my reason for same and I am inclined to think that this is the only motive

there was behind the shooting. (Official Police Report, 1941).

The Lewis report seems

surprisingly obtuse and overly simplistic. Chase resented Johnson merely

because Johnson was obeying orders from Captain Lewis to suspend him and for no

other reason? Unlikely. Johnson went out of his way to avoid causing trouble

for Chase, despite his repeated absenteeism and tardiness. And yet, Chase did not resent

Captain Lewis, who was the individual in power who was actually behind the

suspensions. Why would Chase blame Johnson or direct so much resentment to him,

if he were only angry because of professional differences, such as a

disciplinary action of suspension due to absenteeism?

Lt. Johnson’s affair

with Chase’s young wife was at the heart of the conflict. It appears that this

kind of infidelity was not uncommon at PPB, as during the same general time

period, there was another affair that ended up becoming well known. Though this

controversy was apparently short lived and nothing came of it, it was a cause

for concern. In Frank Springer's 2008 memoirs, he makes mention of an officer

that was getting death threats from another officer due to an affair, which

took place in the early 1940's. Officer A had had an affair with officer B's

wife and there was a lot of threatening and worry over the husband who wanted

to kill the offending officer. This situation was handled correctly. The two

men working the same relief were transferred to different precincts and

eventually the bad feeling between the two died down.

The reality is, if a

patrolman could so easily discover the truth of what had transpired between

Chase and Johnson during the 1920's, in the way that Patrolman Frank Springer

had, why would Captain Lewis not know those very titillating and scandalous

details of the 1922 affair himself? The written report by Captain H. A. Lewis

seems like a blatant whitewash, designed as a personal attack on Chase's

character and on his intelligence. It’s clear that Chase was burnt-out with

police work, in poor health and may have been frustrated with certain aspects

of the command structure but there is no evidence that he was a bumbling idiot

either. The personnel file indicates Chase was skilled as an “excellent

hunter,” a fisherman, farmer and overall outdoorsman. He had worked as an

Express Messenger and was described by one man who had been involved in a motor

vehicle altercation with him as “a clever driver.” To be proficient in all of

these things one must possess and maintain a certain level of intelligence and

savvy. No, there was far more than just a resentment of authority or discipline

at the core of Chase's grudge against Phillip Johnson. Far more.

Frank Springer recalled

the aftermath of that day in May 1941, “Chase then got into his car and he

drove about 25 miles out to a little farm where he grew up. Then he shot

himself. It was a murder-suicide. It was written up in the True Detective

Magazine, and they titled the article, “The Mad Mutiny of the

Kill-Crazy Cop.” Nothing could have been more wrong than that. All the

stories about the both of them were wrong. I've told the truth of it,”

(Springer, 2008).

After Blaine Chase shot

Lt. Phillip Johnson, leaving him to die less than 10 minutes later, and fled in

his black coupe, he drove to Clackamas near Barton and Logan, Oregon, where

he'd been born and raised. Just beyond the Barton Bridge, chase sat in his car,

alongside the Clackamas River. Who knows what he did there? Did he rage to

himself? Did he replay the killing in his mind? Did he remember his young bride

Venola, during their short-lived happiness? Did he recall the day they were

married and exchanged their wedding vows? He would have been 37-years-old then,

Venola only 18.

It is possible

and even likely that he wept, bitterly recalling all the various

losses he'd experienced in his life, and wondering in dismay, what it all

meant, if anything. The detectives suspected he'd be heading to Logan. Word

must have gotten around that he still had family there and that it meant

something to him, as he'd been raised there and went there regularly to fish

and hunt with family members and friends. Blaine Chase would go to the one

place he'd been the happiest in life, before he had headed off to the big city,

to try his luck so many years before.

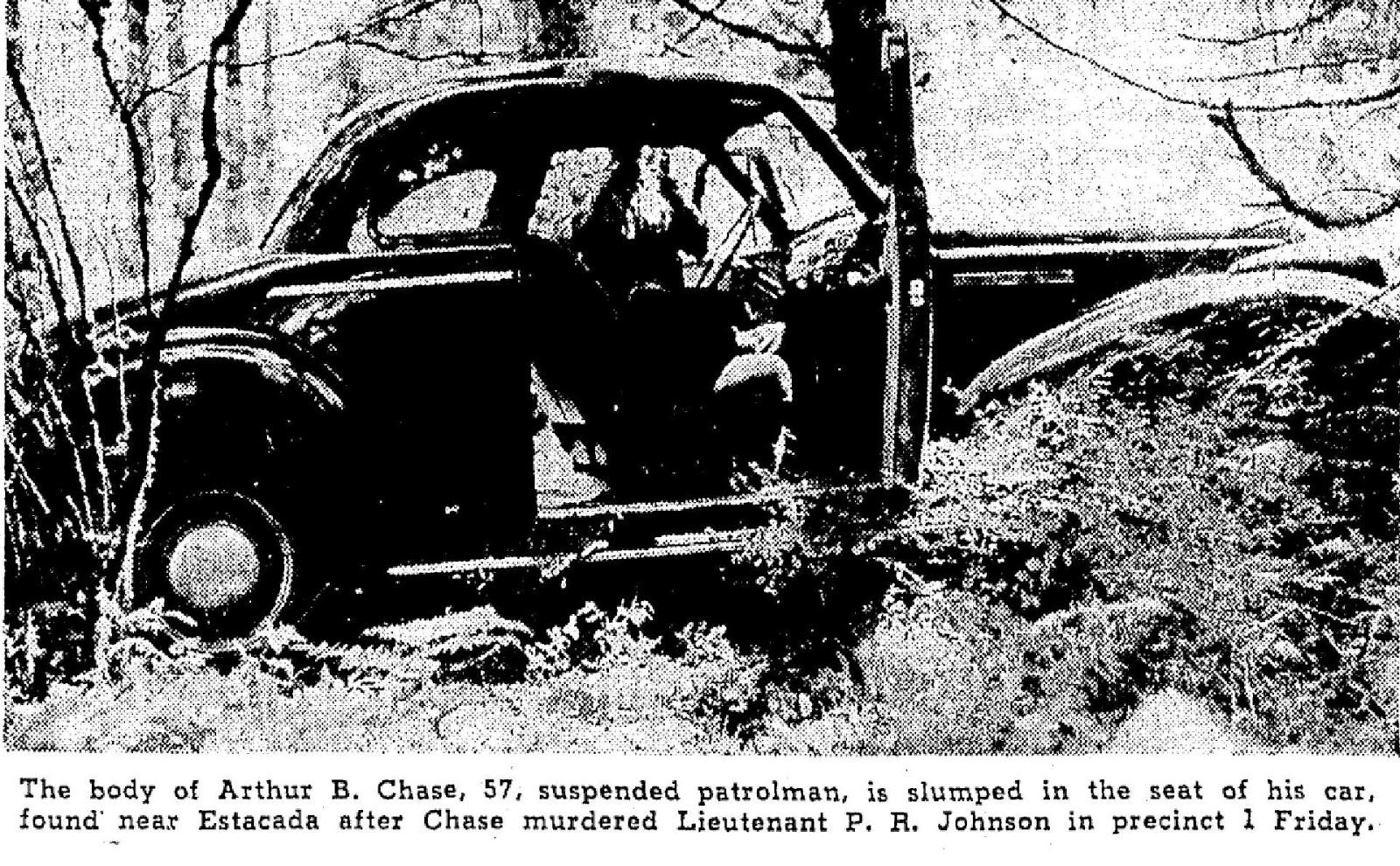

Less than 300 feet from

the ramshackle homestead he'd been raised in, and five hours after he'd

murdered Phillip Johnson, Chase ended his life, shooting himself just behind

the right ear with his Smith and Wesson .38 service revolver. The bullet exited

his skull and became lodged in the top portion of the car. The detectives

Nelson and Abbot had been looking for him in the Clackamas area for hours,

since 6:00 am, along with a Lt Pat Moloney. Was it possible Chase knew they

were in the area, searching for him? Was it possible he heard the distant wail

of their sirens as they combed through the Logan/Barton areas? Chase locked

himself in his car, locking both doors and forcing the police to break into it

later, to gain access to his deceased body. He would not make it easy for

anyone. He would rebel up until the very last. When they finally did break into

the car, they found his service revolver still gripped tightly in his right

hand, his body slumped over in the front seat.

What can we learn from

the story of Patrolman Arthur “Blaine” Chase and Lt. Phillip Raymond Johnson?

Is there a lesson to be learned in this story somewhere? At a time when police

officer's did not have a union or a pension, (or any form of

emotional or psychological support to help them process the burn-out and

inevitable heartache associated with long-term careers in police work) the

necessity and habit was for officers to continue working well past retirement

age and physical ability. This had to have led to feelings of

frustration, helplessness and depression among the older rank and file. Johnson

had been a man pushing 70-years-old and was still working the graveyard shift

to support himself and his wife, Sarah. Chase was a thrice married,

57-year-old, burnt-out policeman in poor health with no other marketable job

skills and no way to support himself other than police work. Both men were

loved by others though, and considered valuable human beings with numerous

friends and relatives who cared deeply about them. Both men were also

imperfect, infallible and highly flawed.

Perhaps the best lesson

to be learned from the story of Blaine Chase and Phillip Johnson is that

sometimes it’s best to steer clear of other men's wives. Sometimes it's best to

consider that a young couple needs the time and the space to grow together,

unencumbered by the desires and intentions of others who may choose to

callously interfere. Along that vein of thought, what would history have to

record had Phillip Johnson never pursued young Venola? Would she and Chase have

developed a strong marriage? Would Venola have matured into a responsible and

loyal young wife and would the 19-year age difference between her and Chase,

have ultimately made any kind of difference? Would they have

had children? Would they have been happy? These are questions

that can never be answered.

Epilogue: After

fired police officer, Arthur “Blaine” Chase killed Lt. Phillip Raymond Johnson,

May 9th, 1941, he fled Precinct # 1 and drove to Logan Oregon. “This being a

wooded country and the birthplace of Chase.” There, he quickly visited his

“nephew” Arthur Wood, who was actually seven years older than Chase, and of

whom Chase was extremely fond. Arthur was the son of either his older sister

Edna or a much older half-brother and had been a source of friendship for Chase

for many years. Chase pounded on the front door of the house, at about 4:00 am,

and ended up waking his nephew and wife out of a sound sleep.

Chase had emptied out

his Apartment and a storage unit less than a week before and had given all his

possession's to his nephew Arthur and his wife. This included an “outboard

motor boat” and all his other possessions, including furniture, clothing and

other odds and ends.

That morning, he

informed his nephew that $2,000 in “insurance” money would be given to a Mrs.

Mary Robinson of Portland, Oregon, at $100 per month. He explained that if

anything happened to her, then the remainder of the money would go to Arthur

Wood and his wife. Mrs. Mary Robinson was a “friend” and providing for her once

Chase was gone must have been extremely important to him.

When asked by his

nephew Arthur, why Chase was leaving his billfold and ID cards, he told his

nephew that he was “detailed on a job that he couldn't have any identification

on him,” but that he would keep in touch. He also told his nephew Arthur that

his doctor had diagnosed him with “heart trouble” and that he had told him he

was “liable to die at any time” because of it. Because of this new condition,

Chase explained that he had left Arthur and his wife $500 each, which they

would inherit at the time of his death through the family attorney. He

explained to them, (and had the week previous) that this was the reason he was

giving them all of his possession's, guns, furniture, money and his boat. That

he wanted to prepare for his eventual death and give them all of his worldly

possessions. It is noted in the police

report filled out by Lt. Pat Moloney that...“Mrs. Arthur Wood is the Ex-wife of

Arthur Chase.” Venola.

Chase left his nephew's

home around 4:30 am, leaving behind the colt .45 automatic weapon he'd used to

kill Johnson and several other guns. He kept in his possession his Smith and

Wesson .38 special, policeman's service revolver. This was the same gun he'd

carried for the twenty three years he'd been a street cop with the Portland

Police Bureau, working the dangerous, mean streets of Portland. After changing

into a set of clean clothes, Chase walked out to his black Buick Coupe, in

front of the house. It is reported that Chase sat in his car, unmoving, for

about ten minutes before finally heading east, driving to that ridge,

overlooking the Clackamas River. After reaching his final destination, and less

than 300 feet from the home he'd grown up in, about a half a mile from his

nephew's home, Chase sat in his car with the .38 in his hand. After the sun

came up, in the morning, between 8:00 and 9:00 am, Blaine Chase put the gun to

his head...

****

Johnson lay dying for

several minutes on the floor of that back office in Precinct # 1 on SE Alder

Street. He was in pain and “groaning” as Officer Cook placed a white pillow

beneath his head, called for the ambulance and attempted to comfort him, all

while Johnson slowly bled out. When Johnson could still speak, before he became

unconscious, he remained silent and said nothing. Even when officer's Cook and

Turley gently questioned him, he looked at them with lucid eyes and refused to

speak. What was he thinking, as he lay there, knowing he was going to die?

Johnson must have learned that Venola had married another man in 1934, after

carrying Chase's surname for thirteen years, as a single woman living alone.

And he must have learned that that man was indeed Chase's own nephew, Arthur

Wood.

What had happened in

those long thirteen years before Venola remarried? Had Blaine and Venola

continued to see each other, secretly perhaps? Had they attempted to reconcile,

only to fail? Johnson must have learned through the incestuously close police

grapevine that Venola had married her ex-husband's nephew, Arthur Wood. How

could that kind of information remain unknown to him?

Did Johnson blame Chase

for his final course of action? Did he understand his hatred? Did he

indeed forgive Chase? Or did he regard the final attack as

nothing more than belated justice? Perhaps a simple accounting of something

familiar, that he felt deserving of in some way? Something unexplainable that

he could never fully sidestep or avoid.

One thing is clear.

Blaine Chase was capable of forgiveness and of love. He was able to forgive his

former wife Venola and not only wish her well with his nephew in their new

married life, but also to provide for her too. It is likely that Chase had

maintained contact with Venola for years in fact, after they had separated. And

he cared enough for her and for his nephew to give them all he had acquired in

his life; which included furniture, a valuable boat, cash and his very last

stitch of clothing.

But what existed in

Chase's secret heart is what finally motivated him to kill Johnson. Love for

Venola and despair over her loss. Johnson had destroyed his initial happiness

in life. He had stolen away from him and sullied his new, young wife which led

to a scandal that Venola apparently struggled for years to overcome.

Mrs. Venola Katheryn

Woods lived for another 39 years, after the murder/suicide of 1941. She died in

1980 in Puyallup Washington at the age of 77. She had worked as a telephone

operator, beginning her career with Pacific Telephone and Telegraph

Company in 1922 and retiring in 1965 from Pacific Northwest

Bell Telephone after 43 years employment. She was a member

of the Telephone Pioneers of America and the Order of the The Eastern Star, a

Freemasonry organization. There is no record that Venola ever had children. She

was survived by only two sisters at the time of her death.

Like

her former lover, Phillip Raymond Johnson and her former husband Blaine Chase,

Venola died in early May, leaving behind unexplained secrets and

questions, only she would ever fully understand.

Acknowledgments: I

would like to thank Ms. Mary Hanson and Mr. Brian Johnson of the Portland

Archives and Records Center of Portland Oregon for their generous help

in locating and copying complete personnel records and

other documents that helped in the writing of this profile. Most

particularly, I would like to thank M. Emily Jane Dawson, from the Multnomah

County Public Library for her generous and supportive assistance in

helping me with important research. Being able to

obtain accurate information, dates and documents has made

the writing of this profile much more interesting, historically relevant

and factual. To these people, I offer my sincere gratitude. -- Theresa Kennedy Dupay.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home